High-Performance Computing Center Stuttgart

With funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Art, HLRS has been conducting a study to plan a Computational Immediate Response Center for Emergencies (CIRCE). Such a center would offer public agencies rapid access to computing resources for large-scale simulation and data analysis during crisis situations. By pursuing dialogue with public officials and testing the approach in a pilot scenario, CIRCE has been gathering information about what specific needs public institutions have, articulating how high-performance computing (HPC) could help to tackle these challenges, and defining technical and administrative considerations that will need to be addressed to ensure that a computational response center can immediately provide the resources and expertise that communities need, when they urgently need them.

On June 11, 2024, the CIRCE team held a full-day symposium in Berlin that presented its preliminary findings to representatives of public administration and experts in disaster response. Complete video of the event is available at the following link: https://www.youtube.com/live/68j7lDTJuyc

In addition to offering general insights into the requirements for establishing a computational emergency response center, the talks highlighted potential applications of simulation, artificial intelligence, and data visualization for crisis management. Data scientists at German federal governmental institutes also enriched the meeting by describing how data is currently used in government planning and decision-making, and offered insights into the practical challenges of navigating Germany’s complex, federalized system of government.

The idea behind CIRCE emerged in 2020 during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Dr. Sebastian Klüsener of the German Federal Institute for Population Research (BiB) approached HLRS for support in running a simulation designed to help manage stresses on the German healthcare system. Together, HLRS and the BiB developed and implemented a simulation that projects intensive care unit occupancy rates in every district across Germany up to four weeks in advance. Using analytical methods developed at BiB and running on HLRS’s Hawk supercomputer, the prediction tool automatically generates reports that are sent to federal ministries involved in health management. During the COVID-19 pandemic the ministries used the reports in deciding when lockdown measures were necessary or could be eased. The collaboration was recognized in 2022 with an HPC Innovation Award.

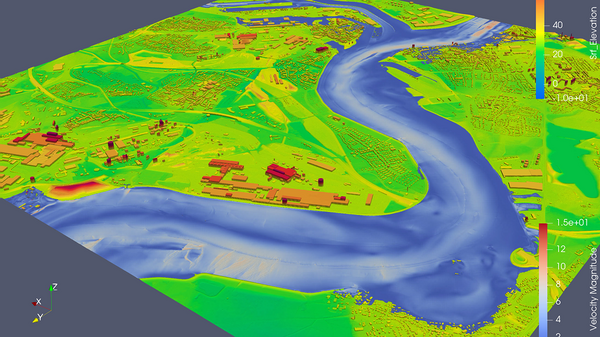

In the CIRCE project, HLRS has been meeting with public officials across Germany to raise awareness of the capabilities of high-performance computing, and to gain perspectives on what challenges they face. This led to a collaboration with the Duisburg fire department, focusing on development of a simulation tool for predicting flooding due to a potential dike breach on the Rhine. This includes investigating the complex question of how barriers at underpasses below a rail line near the river would affect the flow of water through the city’s sewer network. When used during a flooding event, such a tool could help the fire department predict what areas should be evacuated and identify safe staging areas for the deployment of rescue equipment.

As HLRS’s Dennis Hoppe explained at the Berlin symposium, simulation, artificial intelligence, and data analytics are tools that can offer solutions for many kinds of potential crisis situations. HLRS has been involved, for example, in the development of software for simulating weather, geological risks like earthquakes and volcanoes, air pollution, urban energy systems, and windparks. New technologies also make other applications conceivable, he suggested, such as sending aerial drones to wildfires to transmit data to a supercomputing center, which could support firefighting efforts by simulating the spread of the fire in real time. In the HiDALGO2 project, HLRS scientists and their partners also developed tools for predicting flows of refugees fleeing natural disasters or war, an approach that could help public offices to prepare to manage their arrival.

HLRS’s Dr. Ralf Schneider has been leading the center’s collaborations with the BiB and the Duisburg fire department. He sees great opportunities for using simulation in emergency situations, but the key to success is to focus on building the right applications and ensuring that they provide reliable information: “Like a modern crystal ball, the advantage of simulation is that it can predict the future. However, making the crystal ball transparent and understanding what applications of simulation are available are essential points. These are key questions for us right now.”

CIRCE has been exploring two potential types of crisis computing. In the first, supercomputers could provide immediate, automated alerts and data to support emergency response and crisis management. Through conversation with HLRS’s partners in Japan, for example, the team learned that following the devastation caused by the Tohoku tsunami in 2011, buoys were anchored in the Pacific Ocean to sense pressure waves resulting from underwater earthquakes. When an earthquake is detected, a signal is immediately sent to a receiver on land, where first responders assess it to determine if a tsunami is approaching. This rapid response system will create time to issue a coastal evacuation alarm. In other places, similar applications could also support rapid response to floods, forest fires, or the release of toxic chemicals, for example.

Crisis computing can also be used over longer time spans for monitoring potential risks. Weather simulation to predict severe rainfall is a common example, but this approach could also be useful, for example, in tracking the spread of infection during a disease outbreak or to ensure that blood banks contain sufficient blood supply for medical care.

In both of these contexts, one of the first challenges in developing a simulation is to confirm that the necessary data are available. The increasing digital resources of many public agencies — from geographic data, to building information, to demographic data, to environmental quality measurements — offer abundant resources to begin developing simulation tools for crisis situations. According to Schneider, however, the Duisburg project revealed that once a public authority identifies a need, data preparation can still be required to produce the necessary datasets. In Duisburg, for example, one challenge the partners have faced is to develop new maps that integrate two-dimensional and three-dimensional representations of buildings and landscape, as well as other relevant information such as the geometries of bridge underpasses and the topography of the Rhine riverbed. Developing these maps will result in more accurate simulations.

In addition, creating and testing such simulations requires both technical expertise and local knowledge. The Duisburg project has involved experts in flood control and fluid dynamics, and onsite inspections of the area were necessary to confirm that the data input into the simulation adequately represent physical reality on the ground. As the simulation nears completion, Schneider also anticipates that experts will need to review and validate the results to be sure that they are accurate. Only in this way will users of the simulation feel confident that the information it provides is reliable.

Such findings indicate that despite Germany’s existing data and HPC infrastructures, there is still much work to do to ensure that all of the pieces are in place when an emergency arises. Just as fire and police departments acquire technology and undergo training before using them in service, extensive preparation will be necessary to prepare computational tools for emergency response. “We can’t simply expect to be able to manage crises on an ad hoc basis, but need to be active before crises arise,” explained Juliane Braun, Chief Data Scientist of the Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community (BMI). ”We need to define requirements. We need to determine what we are able to model, including the limits of modeling and where adjustments are needed. Only then will we have a toolbox available and know that a particular instrument could help us in the event that an emergency situation arises.”

This means not only developing simulation software, but also ensuring that monitoring procedures, communication systems, and guidelines for decision making are in place before a crisis computing application goes into service. Such preparations will guarantee that data gathering and preparation, calculation of the simulation, and evaluation of simulation results happen quickly and automatically.

Developing urgent computing applications is something that high-performance computing centers like HLRS cannot do alone. In many fields — including, science, engineering, and industry — users bring domain-specific expertise and turn to HPC centers for help when their simulations become too large for the computing resources they have available. What HPC centers can offer is not just large supercomputers that run complex simulations faster, but also staff who support users in operating supercomputers effectively. “We have the expertise that users need to use the machine,” Schneider said, “but users need to bring technical knowledge necessary to analyze the simulation results, including how to deal with discrepancies between simulation and reality.”

In the COVID-19 collaboration with the BiB, for example, Schneider and other technical staff at HLRS worked with Klüsener to optimize his algorithm to run efficiently on the Hawk supercomputer. The simulation leveraged current infection rates, demographic data, and models of how individuals move within and between districts to predict where demand for hospitalization would be most acute. During development of the simulation HLRS helped to address several technical questions, including to determine the optimal size of a reliable simulation, how to improve performance so that the simulation runs more efficiently on Hawk, and how to establish data workflows so that the latest input data automatically flow into the simulation.

Collaboration between HPC centers and public agencies will also require long-term planning to ensure the sustainability of crisis simulations. This includes developing contingency plans for periodic maintenance or upgrades in supercomputing infrastructure to guarantee that crisis simulations are always accessible. At the same time, programmers will need to keep software up-to-date so that input data are still readable, the overall workflow is still executable, and the simulation results are still accurate as supercomputing system architectures continue to evolve.

Koller also cautioned that HLRS does not intend to provide solutions to every crisis simulation problem. “Germany has two other national HPC centers, as well as several smaller but equally capable computing centers in the National High Performance Computing Alliance (NHR),” he said. “Eventually, it will be important to speak with funding agencies to establish a mechanism that defines what is possible and who should have access.” Such decision-making will in part be a question of the extent to which large machines like Hawk are necessary to run specific crisis management applications, as well as generalized procedures for funding emergency access to HPC resources.

With 294 regional districts and an additional 107 self-organized cities, Germany’s public administration is highly atomized. For this reason, it would not be practical or efficient for each community to develop its own specialized solutions. Instead, Braun suggested, increased collaboration among public agencies is needed to develop applications that will be useful across the country. “We need to develop a stronger network so that together we can determine what points need to be negotiated and how best to arrive at solutions,” she said.

In recent years, federal agencies such as the BiB, BMI, and Federal Agency for Cartography and Geodesy (BKG) have assembled large-scale data resources, and provide support in data analysis. According to Dr. Thomas Wiatr, who leads the BKG’s Satellite-Based Crisis and Situation Service, the agency regularly collects geoinformation using remote sensing tools, covering Germany down to a resolution of just 30 cm. The BKG sees itself as a service provider that makes this data available to other public agencies for analysis, including police and fire departments. “In recent years we have seen a significant increase in the number of requests we receive for our analytics products,” Wiatr stated. Such a perspective suggests that data is available and interest in using it for public administration exists.

One big challenge for using supercomputing in crisis situations is how to make better use of such data. Reflecting on the BMI’s work, Braun pointed out, “We have many, very good resources. If we want to improve our ability to manage crisis situations, we need to integrate these resources more closely into one another and we need to work with one another more closely to do the foundational work together.” This could include addressing issues related to data protection and ensuring that data providers reliably make data available on a regular basis.

Christian von Spiczak-Brzezinski has been representing the Duisburg fire department in its collaboration with HLRS, and has been impressed with HPC’s capabilities. “Just looking at what HLRS can do is huge,” he remarked. “But such things are currently not available for many public administrations. From our perspective it is not so important to strive to make better tools, but to attempt to implement what already exists.” Here, the challenge is to improve dialogue between high-performance computing centers, agencies that have access to data resources, and other players at the state and local levels, to improve understanding of what tools are available and to work together to determine how they could be most effectively used.

Better coordination could also have financial benefits. “If every community contacts CIRCE or HLRS directly and develops a custom solution for its own needs, it could end up costing, 3, 4, or 5 times more than if we develop a single concept that is made available to all communities,” Spiczak-Brzezinski argued. This would have the additional benefit of making such simulation tools more consistent, interoperable, and widely available. With respect to his specific project, it could enable better coordination and collaboration among first responders, water management experts, and other stakeholders.

As the CIRCE symposium revealed, simulation offers many ways to support public administrations in managing risks and crises. To realize this potential, however, high-performance computing centers like HLRS will need partners at the local, state, and federal levels who can articulate challenges and commit to developing and implementing solutions. This will require not only that public administrations invest more time in thinking about potential scenarios that could affect their communities, but also improving digital competencies of their staffs. Reflecting on her experience at BMI, Braun said, “We see a wide spectrum of capabilities with respect to data competence. Some public employees can use Excel or do continuing development on dashboards, but in general, data competence needs to be improved. Part of our work involves improving data competency and in the future, networks will also need to be developed to bundle existing competencies.”

As several participants in the workshop pointed out, building interest and competency in digital solutions for managing crisis situations will improve public administration’s ability to conceptualize tools that could make their work easier. Achieving this goal will require outreach and training. Dr. Alexander Bode of KommunalCampus, has been focusing on providing continuing education and digital platforms for employees of public administrations. His goal is to bring digitalization and Germany’s federalized system into harmony. “The problems that communities need to solve are the same all across Germany,” Bode argued. ”Activities like collecting the dog tax or registering an automobile, for example, could easily be centralized and managed at a higher level. This would free up capacity for addressing issues that can only be addressed locally, such as the needs of young people and other activities that demand close interactions with others.” Such a coordinated approach could also hold potential for increasing usage of crisis computing applications.

Speakers pointed out that better communication from experts in digital technology is also needed to address widespread distrust or even fear of new technologies, including artificial intelligence. As Bastian Koller pointed out, specialists in IT and AI do not typically work in local administration, and so broader education is needed to help citizens understand their potential value in streamlining government, including potentially helping to address the shortage of workers currently seen across many domains.

As founder and coordinator of Germany’s National Competence Center (NCC) for high-performance computing, HLRS has experience in identifying and coordinating resources and expertise in simulation, artificial intelligence, visualization, and other HPC technologies. In this role the NCC also serves as a one-stop shop for researchers and representatives of industry who have questions about accessing HPC capabilities. In the future, CIRCE could potentially play a similar role in the field of crisis computing, serving as a destination for representatives of public agencies who have ideas about how HPC could help them in crisis response, but need support connecting to other organizations with the data, expertise, and computing resources needed to turn their vision into a useful tool.

At the CIRCE conference, Koller said that HLRS cannot be alone in building out Germany’s emergency simulation capabilities, but will need to find more data-oriented allies in public administration. “From where I sit, I see the beginnings of a change in thinking,” he remarked in conclusion. “We will have to continue to try to expand our activities and to communicate their results to the public to show them that something new is really happening here. As more people see what we are doing and find it valuable, my hope is that interest will snowball. We will also need to explore how we can increase recognition of these solutions with decision makers from the highest levels to local officials so that they begin to accept this change in thinking.”

— Christopher Williams

To learn more about CIRCE or to explore how simulation could help your community in crisis management, visit https://www.circe-projekt.de.

Complete video from the CIRCE workshop in Berlin is available at https://www.youtube.com/live/68j7lDTJuyc.